Building for the long term

I recently gave a talk to some of my UX (user experience) peers at Shopify, the company I work for. We are a bunch of designers, researchers, content writers, and developers, who work together to build a product and a brand. The following is the script for the talk I gave.

------------

I want to talk to you about building for the long term, through a personal project of mine — my home.

The home I designed, with some help from my husband (who happens to be both an architect and a building scientist). We not only designed it, but also managed construction, negotiated with the city, navigated our way through construction mortgages, maintained neighbourly relations, swung hammers and hung drywall, as well as lobbied with government organizations and documented the entire journey.

But since this is a UX talk, and I don’t have all week, I will stick mostly to talking about the design process.

With that...

For each of us [point to crowd], a lifetime of experience dictates what we think we need in a home. We started out by coming up with a functional plan – the things we thought we needed in our home. Our list looked like a fairly typical realtor spec sheet for a single family home (three bedrooms, two and a half baths). Throughout the design process, we’d challenge our assumptions, but they helped lay the groundwork.

When you decide to rent, or to buy a house, you probably have a vision on how to make it your own. What colours you’ll paint the walls. The artwork you’ll hang on them. Or even what walls you may want to take down one day. You’re likely already building, or decorating, within a box.

But what if you had no box? Where do you begin? How do you define your box?

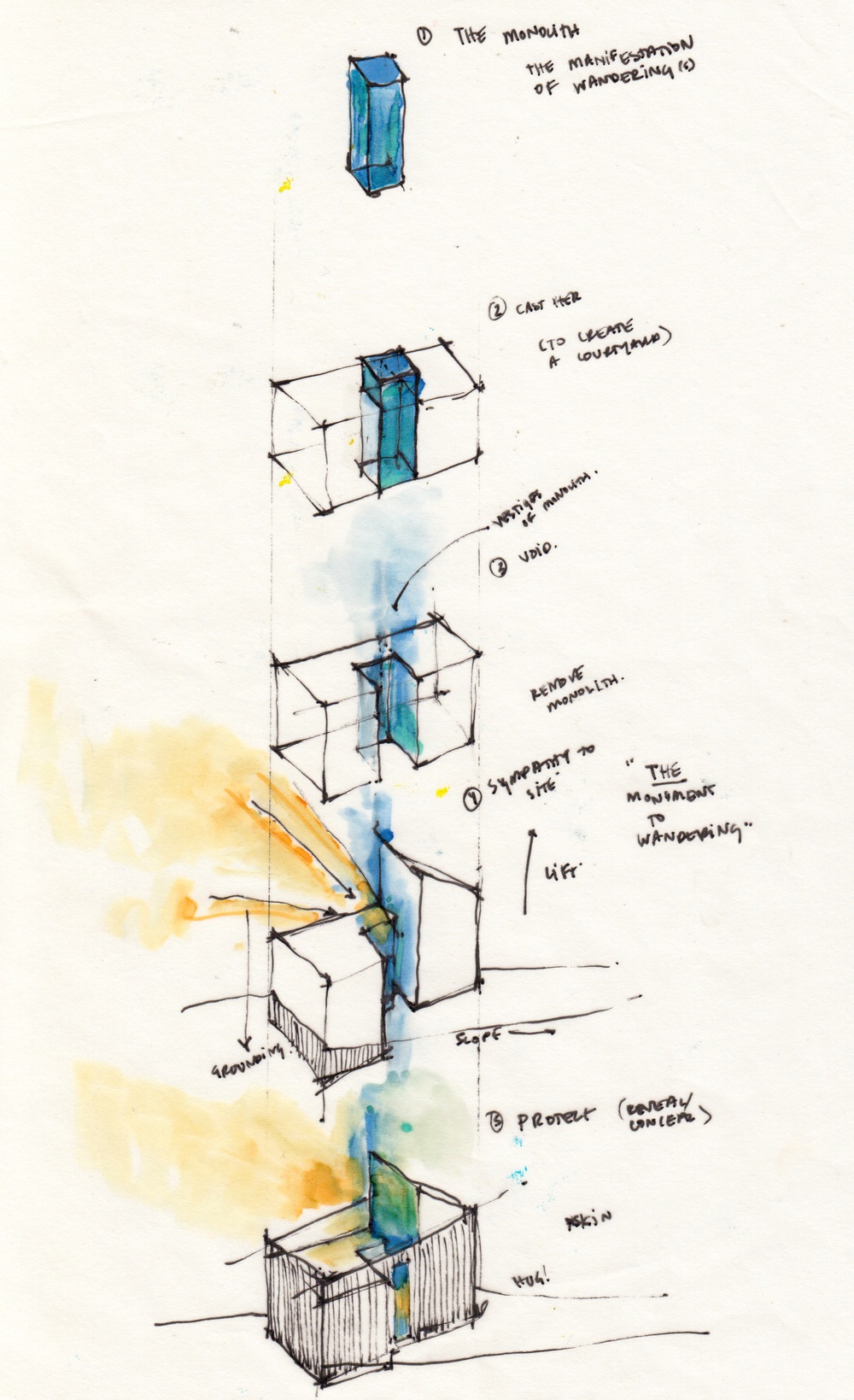

We started by defining our parti, which is architectural lingo, for a concept. It became quite introspective. Who am I? Who are we? This was actually dead easy for my husband and I to agree on. In a previous life, we had spent the better part of two years as wandering vagabonds, traveling the world together slowly, overland, with no destination in mind (and no airplanes). We were onboard with the idea that the journey is part-in-parcel with discovery. We wanted to imbue the house with that same ‘wandering spirit’.

Great, our visions aligned for the parti. But how do you capture ‘wandering’ in a fixed, static, object. The two are seemingly at odds.

Along our travels, we made notes on spaces, lighting, moods, and objects that we were drawn to. We loved the courtyard architecture of southern Spain and Morocco. The way the hallways and staircases wrapped around the pen courtyard, which became the heart of the house. We loved Moroccan lanterns and Moorish patterns. The connection to the outdoors and rooftop gardens. The sense of discovery and chaos wandering through a souq followed by the sense of safety and calm as you passed through the threshold, leaving the outside world behind.

But we don’t live in Morocco. We live in Ottawa.

We channeled this inspiration into something that fits our climate, our lives, our land, our modern aesthetic, and our budget. A design concept started to emerge, with what we named ‘the void’—our monument to wandering. The void became our interior courtyard and grounded the home, while the surrounding living and circulation spaces lifted it upwards, providing unique views and discoveries along the way.

Concept was crucial at the outset for grounding future decision making. It is THE THING that ensures the final product is cohesive. It’s not that you need to be able to guess the concept if you were to walk into my home, but you should just see that it works. The concept results in a cohesive and subliminal continuity that can be felt even before it’s understood.

Now let’s bring this back to ‘building for the long term’.

If you love something, like a favourite pair of jeans, you’ll hang on to them longer. What makes you love those jeans? The style. The fit. Probably. But if the quality doesn’t hold up, no matter how good they look, you’re just not going to keep them.

What you want is a pair of jeans that you love AND that are well built. They will last longer because of their quality, but they will also last longer because you take care of them. The front ass-thetic end and the back end need to hold up.

Having a deep understanding of the back end – how our house would perform and get built, was integral and complimentary to our design process. Again, we live in Ottawa. It’s an extreme environment. Energy prices are skyrocketing. And we are killing our planet. Building for the long term also means building sustainably and reducing our energy dependencies, so there’s some planet left for our kids and our kids’ kids. This is very important to us. Which is why we decided to build to the Passive House standard.

What does that mean? It’s quite simple really, which is why I’m so on board with it. It involves making your house super insulated and airtight. So that the heat you generate, stays inside the house. Then you add to this a super high efficiency ventilation system that provides fresh air but still retains the heat in the house. Essentially, that’s it - that’s Passive House!

My husband uses a really good winter coat analogy when describing Passive House principles. Think about winter here in Ottawa. Now think about wearing a spring coat outside, during winter. In order to stay warm in your K-way, you’ll have to work really hard and run your little heart out. Now think about wearing a Canada Goose parka instead. It makes more sense, doesn’t it? The K-way spring coat is a house built to code. Our house is the Canada Goose parka.

Our walls are rated at a nominal R-96. The newest building code is only R-24. They are 2’ thick. We will heat our home through solar gain and by simply living in it: showering, cooking, and being human. Because the heat will stay in the house. Any makeup heat will be produced by a heater with the equivalent output of a toaster oven.

One of the other ‘measures’ for Passive House is comfort. Have you ever thought about what makes a space feel comfortable? Well the Germans have. They actually have calculations for this.

One of the things they’ve taken into account are thermal gradients. There shouldn’t be any. Meaning the surface temperatures of everything in our house should be even. We will be able to sit an inch away from a window, naked, on a -30• day and say ‘f you’ to winter.

Another comfort measure is the velocity of air movement. You shouldn’t be able to detect it. No drafts.

As added bonuses to building this way, the air quality and sound quality are super quality. Because our house is so air-tight, the air we intentionally circulate passes through three controlled filtres, ensuring my family is breathing clean air at all times. No more air leaking in through rotting wood, allergens, dust or whatever else might be stuffed inside wall cavities. And because our walls are so thick and insulated, even in downtown Ottawa, next to busy roads, our house is as quiet as a mouse. When we close our windows, it feels like we’ve left the city behind.

Passive House. Sounds pretty good doesn’t it? It just makes so much sense to us. Understanding that this was the best possible way to build was key at the outset of our design and enabled us not to see it as an obstacle, but as an opportunity.

Passive House became our framework to design within. The architecture needed to operate within this framework, not against it, yet not afraid to push against the ‘rules’ of the standard.

When design concept and engineering came against each other, these were the opportunities for greatest creativity. For example, instead of thinking of our 2’ thick walls as lost square footage, we started thinking about window seats, and counter tops and ways to use them to our advantage. Some of our most creative details are the result of our 2’ thick walls.

The success of the house, and what makes it built for the long term, is this harmonious marriage.

The build has paralleled my start of my journey with Shopify. We broke ground on the house about a year ago, and have been living in the house for a few weeks now. Somehow we survived. And are beginning to feel the benefits of our hard work. There are still many things that need doing. We have no doors. We need landscaping. Lots to unpack. We have yet to hang things on walls and take the magazine photos. None of that really seems to matter at the moment though.

The real payoff is seeing our kids in the space. The house is like one giant, indoor jungle gym for them. The instant we moved in, they were at home. Moving through the spaces, up and down the stairs with ease, filling it with their creativity and energy. For them, to be able to grow up in a house like this, is where we’ll really see the benefits in building for the long-term.