Foundation Construction Details

Slab and foundation/basement walls with insulation and frost skirt

With the slab poured and the ICF well under way, I thought I would write a quick post with visuals explaining the construction methods and materials being used. I've created some images to go along with all the photos we've been posting to hopefully add some clarity to what you've been looking at so far!

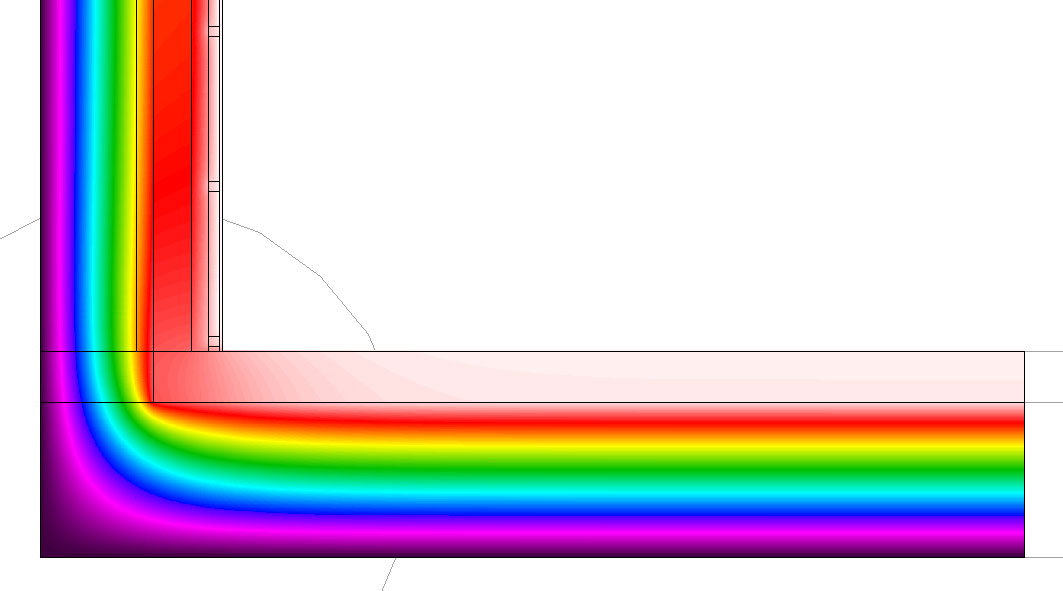

The images above and below show the concrete foundation and foam insulation as it will be once completed. The image below has labels calling out the various layers.

Components of the foundation

The biggest difference between our foundation and a typical residential foundation is the lack of concrete footings. A typical foundation would pour strip concrete footings right onto undisturbed soil, then pour the concrete walls, and finally pour the slab inside the walls. In our home, the slab is poured before the walls and will actually support them, which is why it is so much thicker (8" instead of the standard 4") and has so much steel rebar in it. It is also completely contained within the foam insulation tray, eliminating any thermal bridging through the concrete to the ground. The end result of this is a concrete floor that will retain the heat it absorbs from the house above, rather than simply dumping it through into the ground.

The walls on top of the slab are made up of three layers. First is the ICF (insulated concrete forms) from Nudura. These are like Lego for grow ups. They snap together to form the walls and are held apart by integrated webbing. The cavity is 6" wide and on Friday we will be pouring it full of concrete. Watch for photos this week showing the alignment system that will ensure the walls are straight and true as the concrete is poured.

Once the concrete is poured and the walls straightened, we will be adding two more layers of foam from Styrorail to the exterior to build up the insulation value of the walls. The first layer has horizontal wood strapping embedded, and the second layer will cover this wood and effectively embed it in the middle of the wall. The foam will be glued in place using PL 300 glue, which is specifically formulated not to deteriorate the foam over time. The horizontal wood strapping gives us something to tie back into when we go to install our siding above grade.

The slab poured and the first layer of ICF in place.

Now let's talk about the big white elephant in the room: why so much foam? The amount of insulation is one of the trade offs required to achieve passive house performance on such a challenging site. Because of the limitations of orientation and south-facing window areas, we have to compensate by beefing up the thermal envelope more aggressively than you might find in other passive house projects. The final thickness was determined after several rounds of refinement of the energy model (using PHPP for those keeping track). The really nice thing about this configuration is that all of the concrete is on the warm side of the thermal envelope, where it will hold its warmth, and is protected from expansion and contraction. This alignment becomes especially important when we get to the design of the framed walls above...more on that soon.

ICF at the end of 1 day's work.